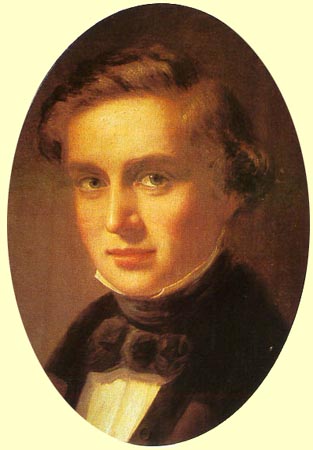

Robert Schumann, one of the greatest Romantic composers, was born in Zwickau, a part of South Eastern Germany. However, Schumann did not start out as a composer. Much like other young men and women, he grudgingly followed the advice of his parents in schooling, in his case law school -- a practical pursuit according to many people. If you remember, G.F. Handel first started studied to become a lawyer as his dad asked him. While at law school, Schumann spent most of his time studying not law, but the piano. He was encouraged in his piano pursuits by Friedrich Wieck, Schumann's soon to be father-in-law. Wieck was a well known piano teacher and father of a gifted piano prodigy, Clara. Around this time, Clara, the future wife of Robert Schumann, was just starting her piano career when her father took Robert Schumann on as a student. Unfortunately, his dreams of becoming a concert pianist were shattered when he injured the muscles in his hand. Not to let this get him down, Robert channeled his energy into creating beautiful compositions for the world to enjoy. For Schumann, this was a period of prolific composition in piano pieces, which were published either at once or, in revised forms, later. Among them were the piano cycles Papillons and Carnaval (composed 1833–35) and the Études symphoniques (1834–37; Symphonic Studies), another work consisting of a set of variations.

In 1834, Schumann had become engaged to Ernestine von Fricken, but started falling in love with Clara Wieck. Clara liked him too, but obeyed her father when he ordered not to date Schumann. So for 16 months Schumann could not see Clara, so he composed more music. He wrote the great Fantasy in C Major for piano and edited the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (New Journal for Music), a periodical that he had helped to start in 1834. But Schumann did not stop liking Clara, so he got courageous in 1837 and formally asked Clara’s father for permission to marry her. Clara's dad, Wieck, did not say "no" but he also did not say "yes;" he evaded Schumann's request. Eventually, Robert and Clara were married in 1840.

By guest author: Matthew F.